What you need to know about buying a private island

If you’ve always dreamed about owning an island, it may be less of a pipedream than you think.

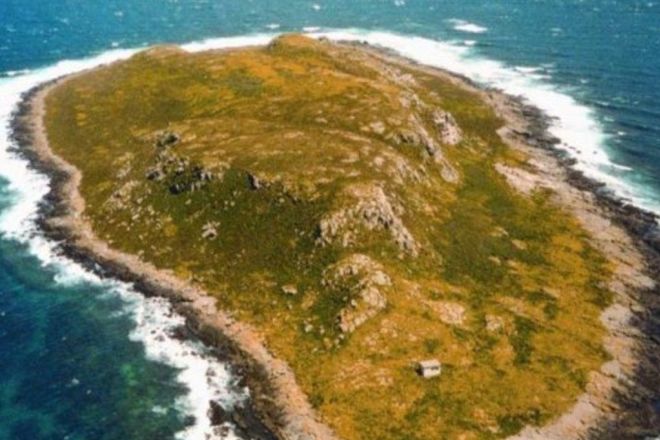

Sales of entire islands are rare, but they do become available for purchase on occasion, presenting a unique opportunity to develop real estate in sought-after locations.

Private Islands Online Australia director Richard Vanhoff facilitates the purchase or lease of islands and manages their sale and acquisition in Australia and the Pacific region. He’s sold islands off the coast of Australia, as well as in Vanuatu and Fiji.

Vanhoff says people buy islands for all sorts of reasons, either for private or commercial use.

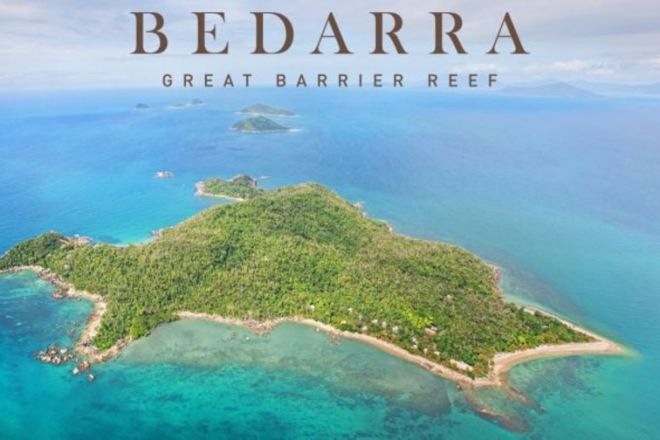

For commercial investors, private isles offer a place to develop real estate, such as a resort or holiday park, with a focus on strong returns on investment for their shareholders.

Development rules for private islands

Just like land on mainland Australia, islands are subject to zoning regulations and are approved for different uses.

“If it’s available as a commercial site,” Vanhoff says, “you have to go through the normal practices that you would do commercially outside any main town.”

In some cases, development approvals are already in place, and investors will need to provide capital to get the project running should they wish to continue with the approved plans.

Vanhoff says the good news for commercial operators is that “there are a great deal of incentives available, particularly in the last couple of months, for commercial operators to develop resort-style development because we just don’t have enough”.

Buying v leasing a private island

There are two ways to buy an island: through a freehold or a leasehold agreement. A freehold means the land is owned outright, much like a house, but these are rare.

Most islands change hands under a leasehold agreement, where you buy the right to occupy the land for a specific fixed term.

In some cases, both freehold and leasehold agreements are available on the same island.

There are typically three types of leases available on the commercial sale of islands: fixed-term, rolling and perpetual.

“There’s a term lease, which may be for 20 years,” Vanhoff says, after which time the lease may be renewed for another set period.

“Then there’s the rolling lease, which could be for 50 years. Every 50 years, it automatically rolls over to another 50 years, so you don’t have to bother yourself or the government in advising them that you want to renew it. It does that automatically.

“The perpetual lease is generally for a little bit longer.”

A well-known example of a perpetual leasehold is Hamilton Island in the Whitsundays, which is held under a 99-year perpetual lease from the Queensland government.

“The benefits are that there’s a great deal of tax deductibility on a lease, particularly if it’s a commercial operation,” Vanhoff says. “You’ve got the payment every year, which is basically a rental, which covers everything but council rates, so you still have to pay your general council dues.”

Council rates apply to islands as they would to any other commercial or private property, but are generally low because councils don’t offer island owners much in the way of services.

Power is typically generated on-site using solar, batteries, generators or both, and, depending on what amenities exist on the island, owners may need to manage their own water and sewage as well.

Like all property, the cost of an island can vary hugely, but there are more affordable options available in the form of leaseholds, should island life be calling.